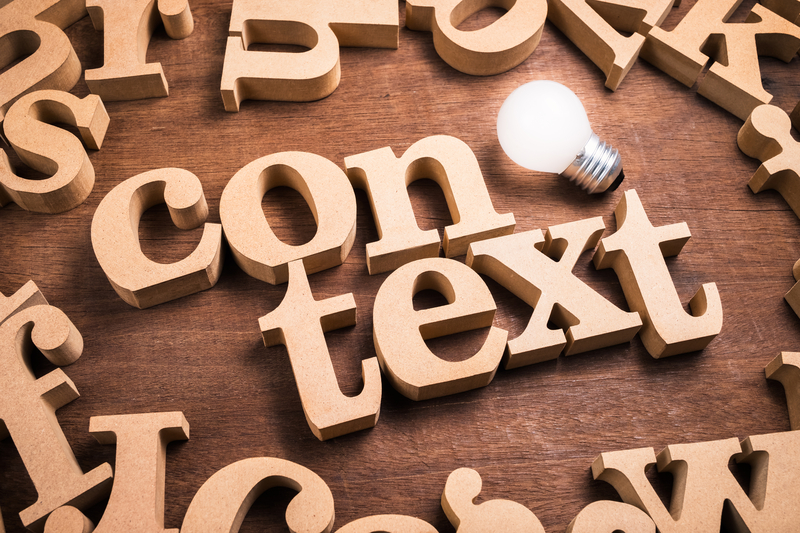

It was an easy, sun-splashed Sunday morning on the shores of Bagac. The tide was retreating, baby crabs were stretching their tiny claws, and the waves hummed a gentle rhythm against the sand. Six fishermen stood in saltwater, their nets spread wide like hope itself. Today, they prayed the sea would be generous—or at least kind enough to fill a few bowls back home.

After half of the crew on the motorized banca laid the net in a gentle crescent, the others began slipping into their handmade harnesses—sturdy contraptions that looked more at home in a weightlifter’s gym than at sea. Each belt was strapped around the waist, then latched to the nylon rope to spare their calloused hands from rope burns. It was a fisherman’s version of armor—simple, practical, born of countless mornings like this.

Half an hour later, the sea began to surrender its secret. The edges of the net rose from the water, glistening with promise. The men leaned in, faces taut with anticipation. But the promise was thin—only a few fish flailed against the mesh. “Not the spread of the net,” as some would say, “but the sea that yields the catch.”

And lately, the sea has been stingy.

Just beyond the horizon, past the peninsula where the ghostly Bataan Nuclear Power Plant still looms, lies Scarborough Shoal—a name that now swims with politics. There, richer fishing grounds await, but so do the gray hulls of the Chinese coast guard, guardians of a claim the world has already dismissed.

So, the fishermen of Bagac stay close to shore, casting their nets not just into water, but into uncertainty. Their small boats float on the edge of geopolitics—where hunger meets sovereignty, and survival is a daily act of quiet defiance.

Here, in Bagac, the sea still feeds—but only those brave enough to keep asking.